Caravaggio: The Revolutionary Master of Light and Shadow

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610), known simply as Caravaggio, stands as one of the most revolutionary and controversial figures in the history of Western art. A pioneer of Baroque painting, his radical naturalism, dramatic use of chiaroscuro (contrasts of light and shadow), and unflinching portrayal of humanity transformed the trajectory of European art. Caravaggio’s life was as turbulent as his paintings were groundbreaking—marked by brawls, murder, exile, and an untimely death. Yet, his legacy endures as a testament to the power of art to confront, provoke, and illuminate. This comprehensive exploration delves into Caravaggio’s life, artistic innovations, masterpieces, and enduring influence, offering a detailed portrait of the man who reshaped the visual language of his time.

Introduction: The Enigma of Caravaggio

Caravaggio’s art defies easy categorization. He was a painter of saints and sinners, sacred narratives and street life, divine grace and human frailty. His works are characterized by visceral realism, theatrical lighting, and psychological intensity, qualities that polarized his contemporaries but ultimately redefined Baroque aesthetics. Rejecting the idealized beauty of the Renaissance, Caravaggio dragged the divine into the grit of everyday life, using ordinary people—prostitutes, laborers, even himself—as models for biblical figures. His technical brilliance and rebellious spirit made him both celebrated and reviled, a dichotomy that persists in modern scholarship.

Chapter 1: Early Life and Formative Years

Birth and Origins

Caravaggio was born Michelangelo Merisi in 1571 in Milan, though his family hailed from the small town of Caravaggio in Lombardy, from which he later took his name. His father, Fermo Merisi, was a minor nobleman and architect-decorator, while his mother, Lucia Aratori, came from a prosperous local family. The plague of 1576–1577 devastated Milan, claiming Caravaggio’s father and grandfather, forcing the family to return to Caravaggio. This early exposure to death and suffering may have shaped the artist’s later preoccupation with themes of mortality and redemption.

Apprenticeship in Milan

Around 1584, Caravaggio began a four-year apprenticeship under Simone Peterzano, a Milanese painter who claimed to be a student of Titian. Milan’s artistic environment was steeped in Counter-Reformation fervor, emphasizing emotional engagement and clarity in religious art—a philosophy that would deeply influence Caravaggio. His early exposure to Lombard realism, with its focus on everyday detail, and Venetian colorism laid the groundwork for his later style.

Flight to Rome

In 1592, following a violent altercation (possibly a duel) that left a police officer wounded, Caravaggio fled Milan for Rome. Arriving penniless, he initially worked as a studio assistant for lesser-known artists, painting flowers and fruit. His talent soon caught the eye of influential patrons, including Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, who became his first major supporter.

Chapter 2: Artistic Breakthrough and the Roman Years

Early Works: Genre Scenes and Symbolism

Caravaggio’s early Roman works focused on genre scenes that blended realism with allegory:

- The Cardsharps (1594): A vivid depiction of deception, featuring a young man duped by card cheats. The painting’s psychological tension and meticulous detail impressed del Monte, securing Caravaggio’s rise.

- Bacchus (1597): A sensual, androgynous Bacchus offers wine, his flushed cheeks and grimy fingernails subverting classical idealism. The painting doubles as a vanitas allegory, with rotting fruit symbolizing life’s transience.

Religious Commissions and Controversy

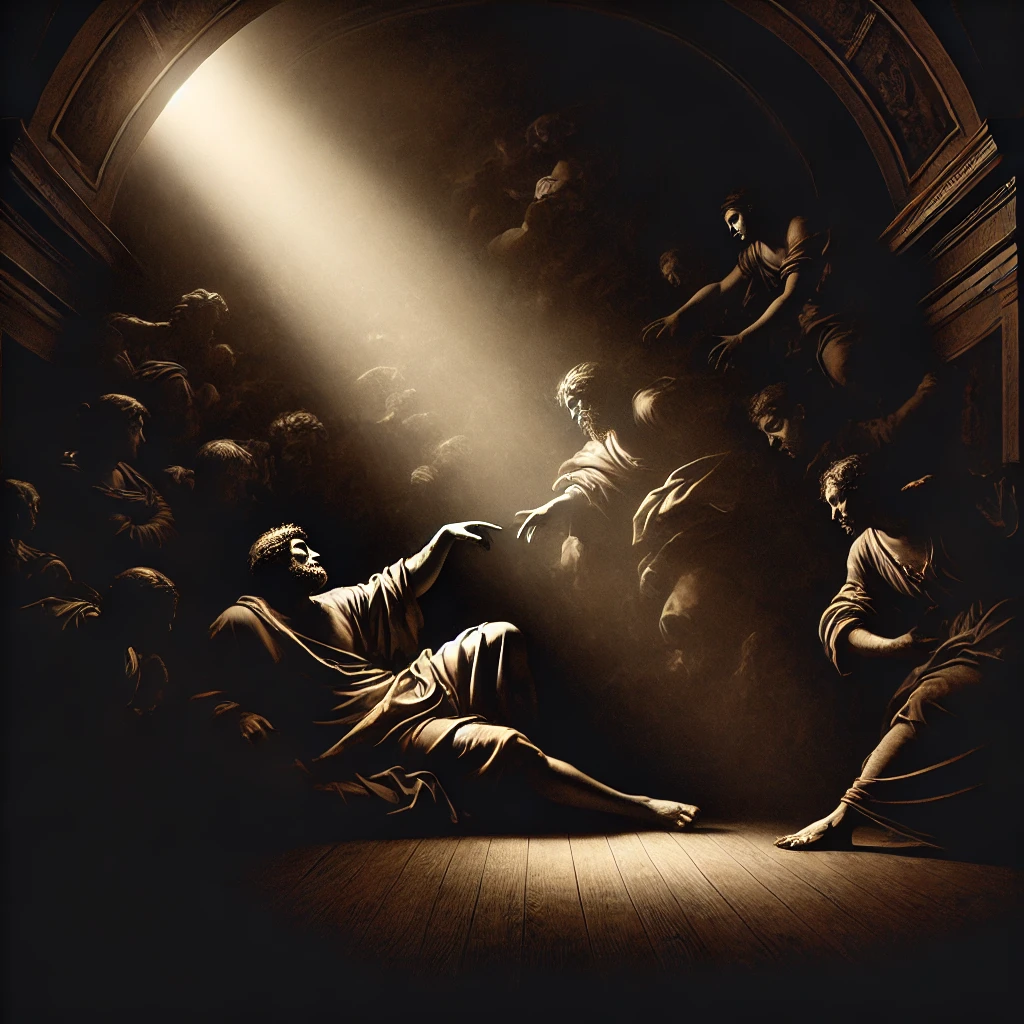

Caravaggio’s first major religious commission, The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600), for the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, marked a turning point. The scene, set in a dimly lit tavern, shows Christ summoning Matthew—a tax collector—to discipleship. The diagonal shaft of light, a metaphor for divine grace, illuminates Matthew’s hesitant face, while the figures’ contemporary clothing ground the sacred in the mundane.

This work, along with The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew and The Inspiration of Saint Matthew, established Caravaggio’s reputation but also sparked criticism. Clerics accused him of sacrilege for using prostitutes and beggars as models for saints and virgins. His Madonna di Loreto (1604–1606), showing a barefoot Virgin Mary receiving pilgrims with dirty feet, was deemed “vulgar” by the Church.

Chapter 3: The Caravaggesque Style – Techniques and Innovations

Chiaroscuro and Tenebrism

Caravaggio’s signature technique—tenebrism—involved stark contrasts between illuminated figures and deep, enveloping shadows. This dramatic lighting served both aesthetic and narrative purposes:

- The Conversion of Saint Paul (1601): A blinding light engulfs Saul (Paul) on the road to Damascus, his outstretched arms echoing Christ’s crucifixion. The composition’s radical simplicity focuses on the spiritual epiphany.

- The Supper at Emmaus (1601): Light rakes across Christ’s face as he reveals himself to disciples, magnifying their shock. The still life of bread and fruit becomes a Eucharistic symbol.

Naturalism and Psychological Depth

Caravaggio’s models were drawn from Rome’s underclass, their weathered faces and calloused hands lending authenticity to sacred stories:

- The Death of the Virgin (1606): The Virgin Mary is depicted as a bloated corpse, mourned by disheveled apostles. The painting was rejected for its “indecorous” realism but is now hailed as a masterpiece of humanized divinity.

- David with the Head of Goliath (1610): Caravaggio painted himself as Goliath’s severed head, his face contorted in agony—a poignant metaphor for his own troubled life.

Composition and Symbolism

Caravaggio’s compositions often broke from tradition:

- The Entombment of Christ (1603–1604): Christ’s body is lowered diagonally, drawing the viewer into the mourners’ grief. The stone slab foreshadows the Resurrection.

- Narcissus (1597–1599): A circular reflection in water traps the self-obsessed youth, symbolizing vanity’s futility.

Chapter 4: A Life of Violence and Exile

The Murder of Ranuccio Tomassoni

In 1606, Caravaggio’s volatile temper culminated in tragedy. During a tennis match, a dispute over a wager escalated into a brawl, and Caravaggio fatally stabbed Ranuccio Tomassoni, a pimp from a powerful family. Fleeing Rome with a death sentence on his head, he became a fugitive, moving between Naples, Malta, and Sicily.

Exile and Artistic Evolution

Despite his turmoil, Caravaggio’s exile years produced some of his most profound works:

- The Seven Works of Mercy (1607): Painted in Naples, this chaotic yet harmonious scene depicts acts of charity amid swirling shadows, reflecting Caravaggio’s own need for redemption.

- The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1608): His only signed work, created in Malta, portrays the martyrdom with brutal realism. The blood pooling on the ground spells “f. Michelan”—a cry for papal forgiveness.

Final Years and Mysterious Death

In 1610, Caravaggio learned that influential patrons were lobbying for his pardon. He set sail for Rome but died under mysterious circumstances in Porto Ercole, possibly from fever, sepsis, or assassination. His body was never found.

Chapter 5: Legacy and Influence

The Caravaggisti and the Baroque Movement

Caravaggio’s style inspired a generation of followers, the Caravaggisti, including Artemisia Gentileschi, Jusepe de Ribera, and Peter Paul Rubens. His techniques spread across Europe, shaping the Baroque’s emphasis on drama and emotion.

Modern Rediscovery

After centuries of obscurity, Caravaggio was rediscovered in the 20th century. Exhibitions like Caravaggio: The Final Years (2005) and Caravaggio & Bernini (2019) reignited global fascination. His works now command record-breaking prices, with The Taking of Christ (1602) valued at over $100 million.

Caravaggio in Popular Culture

- Literature: Derek Jarman’s film Caravaggio (1986) reimagines his life as a queer, anarchic genius.

- Forensic Investigations: In 2010, scientists claimed to identify Caravaggio’s remains through carbon dating, though debates persist.

- Art Crime: His Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence (1609), stolen in 1969, remains one of the FBI’s top art theft cases.

Conclusion: The Eternal Rebel

Caravaggio’s art transcends time because it speaks to the raw, unvarnished truth of human existence. He dared to depict holiness in the midst of squalor, divinity in the faces of the marginalized. His chiaroscuro was not merely a technical innovation but a metaphor for the struggle between light and darkness within every soul. Though his life ended in tragedy, Caravaggio’s legacy burns brightly—a beacon for artists who seek to challenge conventions and expose the beauty and brutality of life itself.

In the words of art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon: “Caravaggio invented a new way of seeing. He showed us that truth is not in the ideal, but in the real—in the grime, the blood, and the grace”.

Art11deco